Plant of the Day Ligusticum porteri (Osha)

Osha, Porter's lovage, Porter's licorice-root, Porter's wild lovage, loveroot, bear medicine, bear root, mountain lovage, Indian parsley, mountain ginseng, nipo, chuchupate

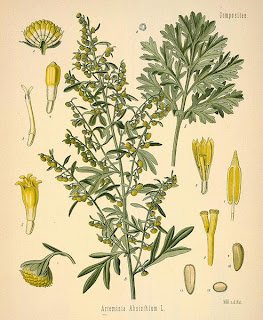

Osha is an herbaceous perennial growing from 50 to 100 cm tall or more. In winter, the above-ground parts die back to a thick, woody and very aromatic rootstock. The plant has deeply incised, elliptic or lance-shaped leaf segments that are 5 to 40 mm in width with larger basal leaves. The white flowers appear during late summer, and are approximately 2 to 5 mm in diameter with five petals. They are grouped in flat-topped, compound umbels and are followed by reddish, oblong, ribbed fruits 5 to 8 mm in length.

Osha is native to mountains of western North America from Wyoming (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah) to the states of Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico. Osha often grows in rich, moist soils in wooded habitats—from pine-oak woodland to spruce-fir forest—but it is also found on slopes and in meadows with drier, rocky soils from1,500 to 3,505 meters ( 4,900-11,500 feet; Cronquist et al. 1997, Welsh 1993, Martin et al. 1998)

Like many plants in the Apiaceae, the flowers are attractive to a variety of insects such as flies, beetles, bees and wasps. However, studies of pollination biology among plants in the carrot family find that there is a distinction between mere visitors and effective pollinators, with the latter being andrenid, colletid and halictid bees (Lindsey 1984) in some cases. Halictid bees have been seen visiting flowers of osha in the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona (M. F. Wilson, observation Sep. 2, 2003). Seeds of osha are not dispersed by animals or wind and most likely remain close to the parent plant when they drop (David Inouye, pers. comm. 2007).

Osha has been used medicinally by indigenous people for centuries and subsequently absorbed into the pharmacopeias of other peoples. The genus contains many plants that are used medicinally in both the Old and New Worlds (Mabberley 1997). The roots have been used in various preparations (tinctures, infusions or teas) and taken internally especially for catarrh, colds, coughs,

bronchial pneumonia, flu and other respiratory infections. Root preparations are used to treat fever, diarrhea, gastrointestinal disorders, hangover, sore throats and rheumatism (Moerman 1998, Reina-Guerrero 1993, Wilson & Felger, in prep., Yetman & Felger 2002). Externally, root preparations were used to treat aches and pains, digestive problems, scorpion sting, wounds and skin infections. The hollow stems have been smoked to break the nicotine habit (Bye 1986, Curtin 1976).

The genus Ligusticum consists of 40-50 species of circumboreal plants (Mabberley 1997). Many are used medicinally. American Ligusticum species have been used as anticonvulsants, to stimulate appetite, and to treat anemia, hemorrhage, tuberculosis, stomach disorders, heart troubles, respiratory infections, earaches, sinus infection and congestion, and other ailments (Moerman 1998). Some Asian members of this genus are important in Chinese, Japanese and Korean herbal formularies. Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. (L. wallichii Franch.), Szechuan lovage root, is used to treat amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, headaches, ischemia and thrombosis (Bensky & Gamble 1993). Many peoples of north temperate regions eat portions of a number of species of Ligusticum raw, cooked as potherbs, or as condiments or spice (Tanaka 1976).