Trail Marker Trees

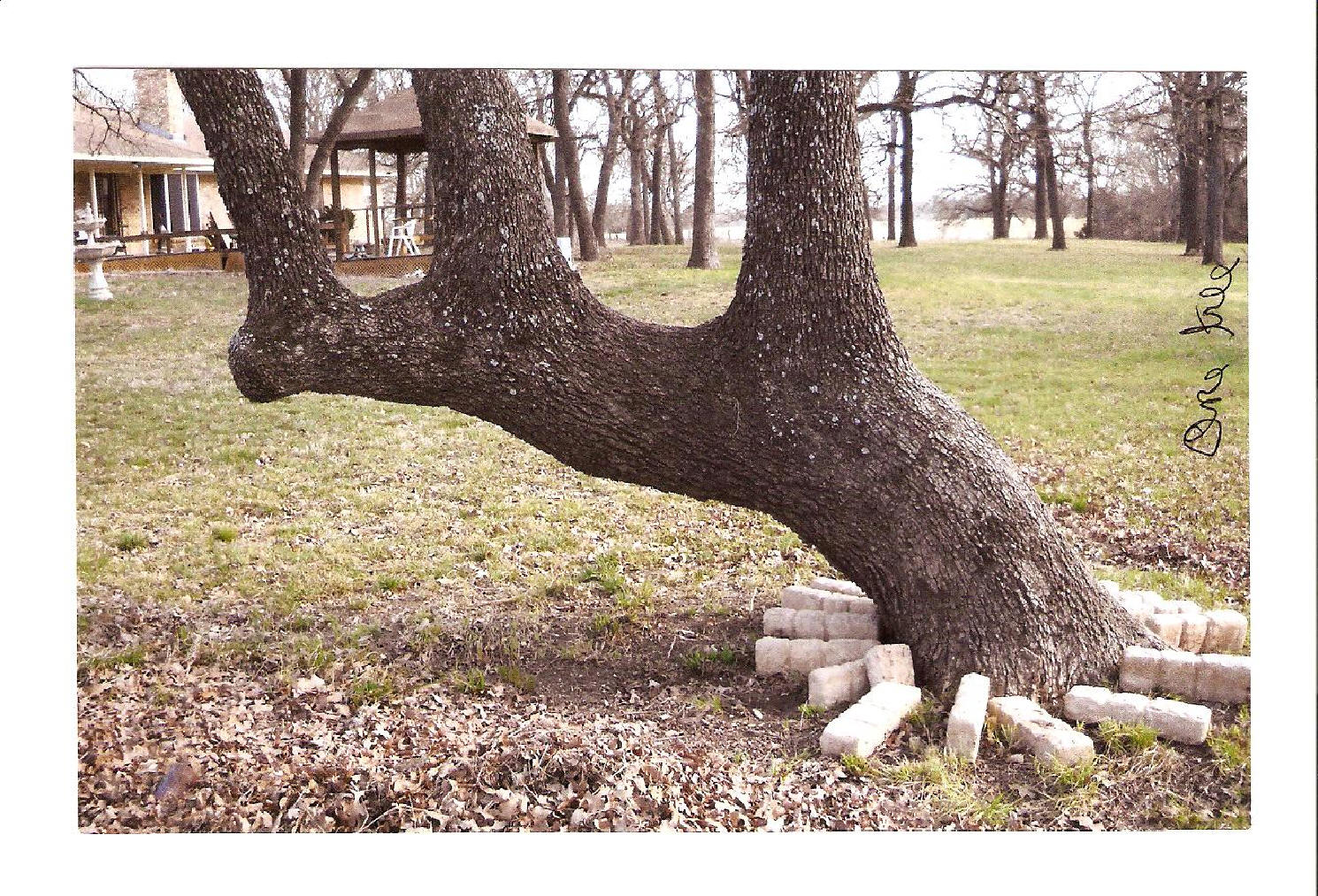

Across the U.S., you can find trees that are oddly shaped. Their trunks have odd kinks in them, or bend at strange angles. While some of them may indeed be simple quirks of nature, most of these trees are actually landmarks that helped guide indigenous people on their way. Native Americans would bend young trees to create permanent trail markers, designating safe paths through rough country and pointing travelers toward water, food or other important landmarks. Over the years, the trees have grown, keeping their original shape, but with their purpose all but forgotten as modern life sprang up around them. Today, we may not need these “trail trees” to navigate, but their place in history makes them invaluable. Imagine the stories these trees could tell.

Although the exact mechanics of how Native Americans bent the trees is unknown, Mountain Stewards has been able to shine light on the basics of the process.

The Indians took a small sapling and bent it horizontal to the ground. The tree was tied to the ground for a year, allowing it to grow into a bend. At the end of that year, the Indians would bend the tree again and begin shaping it for its particular function. Marker trees typically had a “nose” on the front, which would atrophy or be cut off after the initial bending process. The bending process usually took between five and 10 years.

Besides trail markers, the trees served as, prayer trees, medicine trees, campsite markers, witness trees and grave markers. The Utes in the west used Ponderosa Pines as prayer trees. Every year during their spiritual pilgrimage, the tribe would return to their tree and continue the bending process. Once the process was complete, the Utes would offer tobacco to the tree because they believed their ancestors resided there.

The trees also played a part in human healing processes. The cambium layer of bark, inside the outer and inner layer of bark contains as much calcium as nine glasses of milk. Indians in some tribes would eat this bark to nourish themselves to survive the winter.

Many of the trees used as markers in the south were white oaks; these trees have been found to mark water and trails. The Comanche Indians used pecan trees as campsite markers to mark favorable sites with high bluffs and flat ground near water.

Other marker trees known as “witness trees” were carved with messages that only Indians knew how to read. This practice was adopted by early American settlers for use in surveying.